I thought since we all have been glued to the news rather you voted for the new President or not this past election, this blog post was appropriate for the occasion. It was taken from ESPN.com on my blackberry and it's an open letter to President Barack Obama. I hope you enjoy it.

Dear Mr. President:

Every 50 years or so since the rise of the U.S. as an industrial power, someone with your impending job title takes a hard look at the athletic activity of children.

He finds neglect and opportunity.

He takes action.

He leaves the nation -- and, ultimately, the sports nation -- in a better place.

Just over a century ago, it was

Teddy Roosevelt. Ascending to the presidency at a time when America was about to make its play as leader of the free world,

he didn't like what he saw happening with teenage boys. Roosevelt grew up an asthmatic, a sickly boy from polluted New York who made his body strong by embracing a life of vigorous exercise. He wrestled and lifted weights, and he boxed even after moving into the White House.

He worried that the comforts of urban life had rendered middle- and upper-class boys soft and effeminate, raised, as many of them were, by their mothers. They hardly seemed fit, the way he saw it, to take over the businesses that their more manly fathers were hard at work creating. At the same time, the nation needed dependable laborers to pave the expansion into new markets. Sports, and team sports specifically, became seen as a way to indoctrinate immigrant boys into the ways of American capitalism. "Only aggressive sports can create the brawn, the spirit, the self-confidence, and quickness of men essential for the existence of a strong nation," Roosevelt roared.

A half-century later, Dwight Eisenhower was fighting a Cold War that seemed as if it might turn hot on a moment's notice. As a former general, he knew that half of all men who had shown up at draft boards around the nation were considered physically unfit. And a study presented at the

American Medical Association had shown that U.S. children were far more out of shape than their European peers. Over there, kids still walked or rode bikes to school and chopped wood for home heating. In the new suburban America, boys and girls were being driven everywhere. Home chores consisted of making their beds. As for school sports, they were focused on interscholastic competition, the province of the certified jock.

An alarmed Ike created in 1956 what ultimately became known as the President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports, which promoted physical education classes as early as first grade. Intramurals exploded, giving the less athletically gifted kid a chance to compete. Also, the groundwork was laid for passage a few years later of a federal program to help fund the construction or renovation of 40,000 parks and recreation centers in just about every county in the country. Today's baby boomers, the first generation to grow up with an exercise ethos, were the chief beneficiaries of these investments.

Your turn, No. 44.I know you have a lot on your plate, between fixing the economy and smoking out bin Laden. But you've got a big brain, so let me introduce you to another mounting crisis that will require your leadership to solve: That of our sport system at its base. Maybe as you're trying to modernize our schools and mend our health care system, you can think about building in reforms to the opportunities our children have for physical activity.

From the top down, the system looks pretty good. Our pro leagues are thriving, as are the owners of their franchises. Our athletes are worldwide brands -- Kobe; A-Rod; Peyton Manning; the Williams sisters; and, especially, Tiger. From the window of an airplane, our mega-stadiums sparkle like 10-carat diamonds amid urban and college-town landscapes.

But viewed from the bottom up, the setup looks a lot more like the Wall Street we have come to know of late: a system compromised by greed and ignorance, in which the haves increasingly get rewarded at the expense of the have-nots, with the support of government.

To understand where the priorities lie today, start in America's largest burg. Last week, officials for the city and the New York Yankees were hauled before a state assembly committee to justify the most expensive stadium project in U.S. history. The $1.5 billion ballpark is being built on one of those historic playgrounds built a century ago, Macombs Dam Park, whose fields over the years have served countless youth and school teams in the South Bronx, the poorest congressional district in the U.S. The city effectively gave a 22-acre parcel to the richest team in baseball, then allegedly jacked up the estimated value of the land to gain access to $940 million in federal tax-exempt bonds. Now the Yankees have been granted another $370 million in such bonds -- just weeks after signing Mark Teixeira and two other free agents for a combined $423 million.

The city promises to build a series of smaller replacement parks elsewhere. But some won't be ready for years, one will be on top of a parking garage, and another is in an industrial area far from the neighborhood. And we'll see what residents really get once the economy wreaks full havoc on city budgets.

"

In New York City, 70 percent of kids are kicked to the curb at the end of the school day," said Al Bevilacqua, a wrestling coach whose nonprofit organization, Beat the Streets, is trying to reintroduce that sport to public schools using private funding. In the city that pioneered the uniquely American tradition of school sports,

the options for many students are very limited. As an undergraduate at Columbia, you lived in New York long enough to get a sense of the experiential gap between that of a large public high school there and an elite private school such as the one you attended in Honolulu. Well, it's grown. Intramurals and quality P.E. classes are scarce, and only so many kids can make varsity basketball. Do you know how many U.S. Olympians the Big Apple sent to Beijing? Just eight. Four fencers, one boxer, one judoka, one riflewoman and one table tennis player originally trained in China.

Australia, which draws from a population only some two and a half times the size of New York City, won 46 medals.

Just about everywhere in America, inner-city kids struggle to find athletic opportunities. That's true even in places like Miami, with its reputation for producing elite football players. Miami Northwestern Senior High School won the mythical national championship in 2007 with a team that sent more than a dozen seniors to D-I programs, yet the school profile shows most students at the school couldn't pass the annual fitness exam. So is Northwestern a jock factory -- or a fitness flunkie?

You'd never know it from watching pro sports, in which African-American presence has grown, but black teenagers play sports less often than they did decades ago. In 1980, no ethnic group had a higher participation rate, according to U.S. Department of Education statistics. Not anymore. In fact, since then, no group has lost more participants. The obesity crisis is a national problem, but especially in black and Hispanic communities.Those at the top of the sports pyramid aren't unaware of deficits at the bottom. Perhaps no league does more than the NFL, which has created an endowment that spends $25 million a year on refurbishing community football fields in distressed areas, according to a league spokesman. But such gifts are table scraps in the all-you-can-eat feast that is pro sports, where growth has been fueled by billions in public subsidies and tax advantages.

"They're more or less P.R. campaigns," says Scott Lancaster, who ran the NFL's youth programs for 12 years until 2007.

The NFL recently stopped funding one of its main youth programs. Junior Player Development, created by Lancaster, had helped repopularize football in poor urban areas by introducing the game to hundreds of thousands of kids through trained coaches. Many went on to play in college. Now the well-regarded program has been shut down, likely for good. The NFL cites the economy. Lancaster suspects it had more to do with posturing for negotiations with the players' union, a desire to plead poverty where none exists. "They've put youth in the middle and made it a victim," he says.

In tough times, sports funding for kids is always an easy cut. Even in the 'burbs now, school districts are talking about eliminating teams -- or even entire athletic programs. "You're going to see decisions made in the next two years that we've never seen made," one Connecticut high school athletic director told me. Youth sports in these communities will become further privatized, the realm of parents who can afford to sign their kids up for an endless slate of organized activities, from sport-specific camps to private lessons to travel teams with paid coaches.

It's hard to get your mind around how much the sports activity of children has changed since we were boys. As recently as the mid-1990s, the average age at which kids began to play organized sports was 8. Now, many start slipping on uniforms by 5, and after that you rarely see kids playing games without one. When my daughter was in second grade, there were girls on her rec league soccer team who were in their ninth season of soccer, having been signed up each fall, winter and spring since kindergarten (three seasons a year).

By third grade, in some sports, elite travel teams are being formed that stand apart from the in-town rec leagues that historically have provided opportunities for all kids. Ghettoized, the rec leagues begin to wither, while the travel kids go on to dominate varsity rosters. We're effectively holding high school tryouts now in grade school, sorting the weak from the strong before kids even hit puberty.

You seem like a man who can appreciate that youth sport is the most important institution in all of sports, because that's where the magic begins. It's where we learn to love these games, picking up fitness habits and rooting interests that can last a lifetime. But many kids start falling away from sports around age 11 now. The system has become less accessible to the late bloomer, the economically disadvantaged, the child of a one-parent household, the physically or mentally disabled, and the kid who needs exercise more than any other: the clinically obese.

We also risk burning out the "winners" of this premature struggle. It's worth keeping in mind the modern cautionary tale of Elena Delle Donne, the 2008 national high school player of the year in girls basketball. Soon after arriving at UConn with a full ride, she quit the game, later explaining that she had stopped enjoying hoops back in middle school. All those AAU national championships, all those sessions with the personal trainer her parents had hired for her since second grade, led to no return on investment. She chose to walk on instead with a volleyball team at the University of Delaware, closer to home and friends.

Government policies have shaped this landscape. It's tempting to point to Title IX for the spread of scholarship mania among parents, as the amount of athletic aid handed out by NCAA programs has quadrupled since the early 1990s, to $1.5 billion annually. But that law also has been the greatest tool for growing participation since, well, the advent of organized youth sports, by forcing high schools and middle schools to create opportunities for girls.

It's clear that you, Barack, get that.

"I am the father of two young girls who are growing up playing sports and who are the beneficiaries of the doors Title IX opened," you said last year, signaling your intention to strengthen enforcement of the law down to the "pre-kindergarten" level.

Far more problematic is the Olympic and Amateur Sports Act, which charters the U.S. Olympic Committee and makes requirements of the national governing bodies of individual sports. The law asks that the USOC coordinate amateur sports activity in the country, but it's an unfunded mandate, a real bridge to nowhere (which was a specialty of its author, former Senator Ted Stevens). The USOC has focused its limited resources on the elite of the elite, making little effort to push coaches' education down to the youth level. In Europe, coaches are certified and trained in athlete development; here, the scene is dominated by millions of parent volunteers, well-meaning but winging it.

Attrition drops when coaches are trained in working with kids. It's been proven.

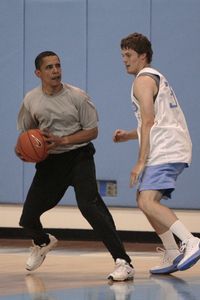

You are no doubt looking for ways to cut, not add to, the federal budget. But look at it this way: The economic consequences of Americans' physical inactivity are huge, costing more than $76 billion a year in direct medical costs alone, according to one academic study. Health care is a major priority of yours, with an emphasis on prevention. There's no better preventative care than finding a sport for life, like those weekly pickup hoop games you'll soon bring to the White House, Cabinet members in tow.A bunch of your advisers got game, from education secretary nominee Arne Duncan (former Harvard co-captain) to attorney general nominee Eric Holder (former Columbia player) to brother-in-law Craig Robinson (current Oregon State men's coach). So get them in a huddle and come up with a new model for grassroots sports, built from the bottom up with a simple premise: sport as a human right, just like education. Here's how to do it:

•

Offer incentives for schools to create more teams, not fewer, which is what is happening in the era of No Child Left Behind, with its strictly academic focus. The least that schools can do is modernize P.E. by connecting teens with local clubs that sponsor lesser-known sports in which they might find success. "You have to connect the national governing bodies with the schools," says Judy Young, a top expert on school-based sports. "Schools just can't teach the full array of 45 sports seen in the Olympics."

•

Restore funding for urban parks and rec centers that have been gutted in recent years. Perhaps you can pay for it with a tax on the pro leagues that do business in these cities and whose empires have been built on the public dime.

•

Rewrite the Olympic and Amateur Sports Act so that Job 1 for the USOC is tending to the base of the participation pyramid. While you're at it, enlist Larry Probst, its new chairman, who comes from the video game industry, to share what he knows about creating games that engage today's children. "A lot needs to be learned about making sports a contemporary experience for kids," says Lancaster, who while at the NFL experimented with hybrid games that married hand-held video with real play. "We're still asking them to play games the way their dads did a generation ago."

The key is getting progressive, not sentimental, about youth sports. Parents just aren't going to let their kid ride a bike halfway across town anymore to play sandlot ball, unsupervised. The murder of Adam Walsh changed all that.And now, you can change it again, for the better. Imagine a Chicago Olympics in 2016 -- the first truly "Sport for All" Olympics, as you can pitch it when the host city is selected in October 2009, deploying an ideal celebrated by the IOC. An Olympics in which national governing bodies like U.S. Swimming and U.S. Badminton already are making new efforts to go into the inner city and get kids involved. An Olympics with a legacy of facilities that will benefit regular athletes, not just elites. An Olympics measured by growth in the number of Chicago kids who play sports into their teenage years and beyond. An Olympics that can cap your eight-year run as a president known for fresh ideas, with a statement in your adopted hometown about the possibilities of American sport.

The moment is there for the taking, Mr. Obama. It's one Teddy and Ike would surely seize.Hope that gets you thinking.

Sincerely,

Tom Farrey

Tom Farrey is the author of "Game On: The All-American Race to Make Champions of Our Children," an exploration of the culture of modern youth sports. The book, his first, was recently named the 2008 Sports Education Book of the Year by the Institute of International Sport at the University of Rhode Island. Tom can be reached at tom.farrey@espn3.com

Youth Fitness Professional in Charlotte, NC

.jpg)